CASTLE JOINTS

The strongest joint in woodworking.

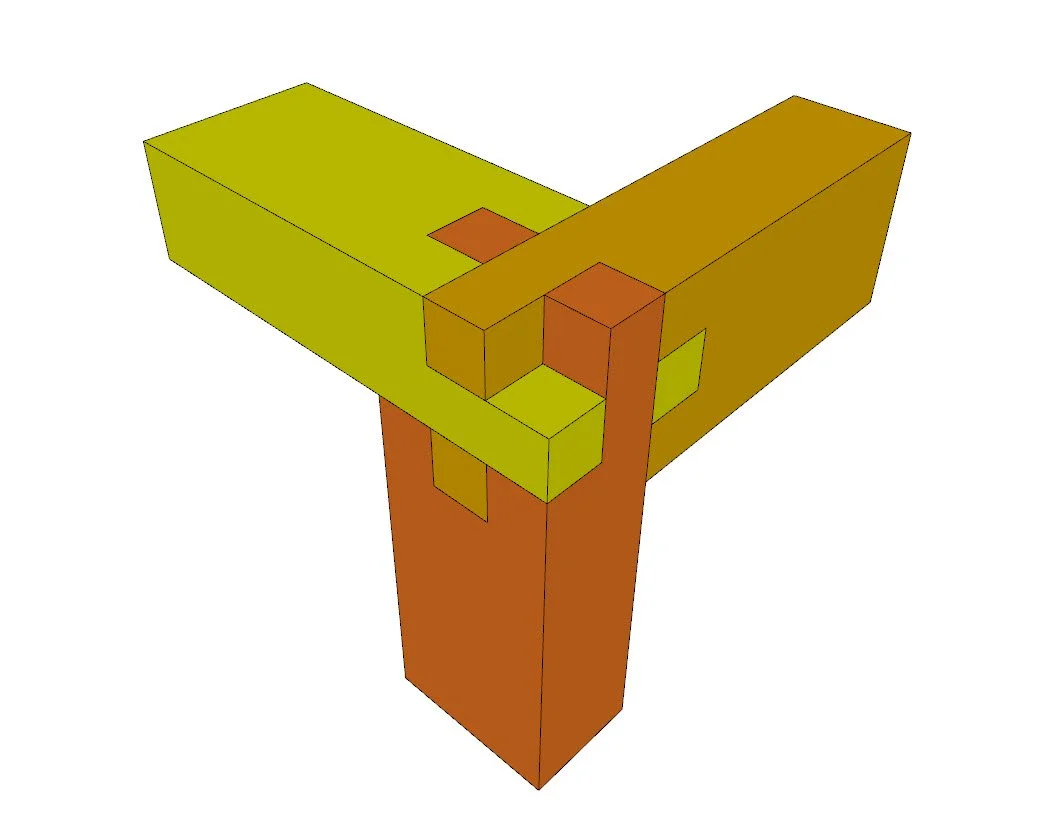

I love interesting joinery. The right joint can be incredibly strong, but it can also be beautiful in and of itself. I think this joint is a perfect example. I call it the Triple-Castle Joint. If I were a gamer, I might call it the Tri-Force Joint. I have no idea who first came up with it, but I love the complexity—at least the perceived complexity. While this joint looks like a puzzle of mortises and tenons that would be frustratingly difficult to cut, it’s actually made from three identical pieces, each containing just four straight cuts.

I first saw this joint when a viewer sent me a link to the 3X3 Custom channel. Evidently, she found the joint on Pinterest in what I can only guess is some type of bed or table. She found it so interesting that she figured out how to cut one on her own using a table saw. I'll link to her video below if you'd like to try it the way she did.

The viewer who pointed me to that video asked how I might approach this. Honestly, I’d probably use a table saw like she did, but since that's already been done, I decided to make it more interesting by cutting it by hand. Through this article, I’ll not only reveal the secrets of this clever joint but also share some hand-sawing tips that can be applied to a variety of other projects. If you want to improve your hand-sawing skills, pay close attention as you keep reading.

The Materials

The materials I used to complete this joint.

Since this was only a demo, I used relatively small pieces of walnut, but this joint can be made at any scale, including with larger beams, as long as you follow two simple rules:

All three pieces must be the same size (not including their length).

The width of each piece must be 1-1/2 times its thickness.

In this case, the thickness is 36 millimeters (yes, calculating a ratio is one of the few instances where millimeters is better than inches), and the width is 54 millimeters—1.5 times the thickness.

This ratio is critical for the joint to work, but it also makes the layout process really simple. That’s good because, at first glance, the layout looks anything but simple. You will see below all the waste that needs to be removed, but it’s all based on that 1.5:1 ratio. This means you can use the workpieces themselves as marking gauges and skip virtually all the measuring.

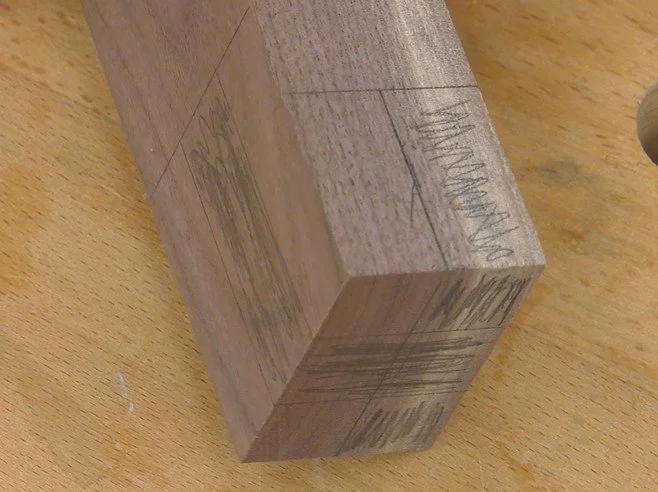

At first glance, the layout looks anything but simple.

Here’s the steps to how I marked mine:

With a workpiece laying on its edge, mark both the front and back faces.

Turn the workpiece to lay flat, and scribe a second line on all the front faces and both edges.

Still laying flat, mark the front faces first while on one edge, then flip it end-for-end to the other edge. This divides the face into thirds. Repeat this on both the front and back faces of all the workpieces.

A similar process is used to mark the end grain of all the workpieces, again dividing it into thirds.

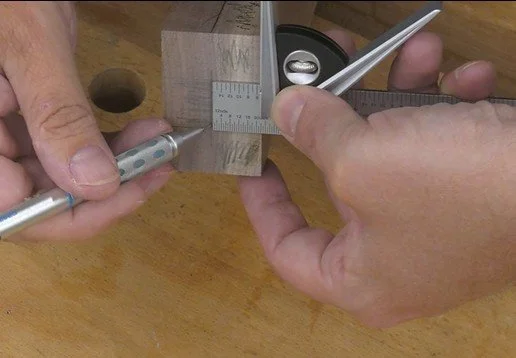

Next, I used a combination square to draw right down the center of the end grain, dividing those three sections into six.

Finally, I used the same square setting to bisect both edges of all the workpieces.

Once again, you can see I’ve colored in all the waste areas that need to be removed. It looks complicated, but it's really not. If you copy what I did below, you’ll be fine.

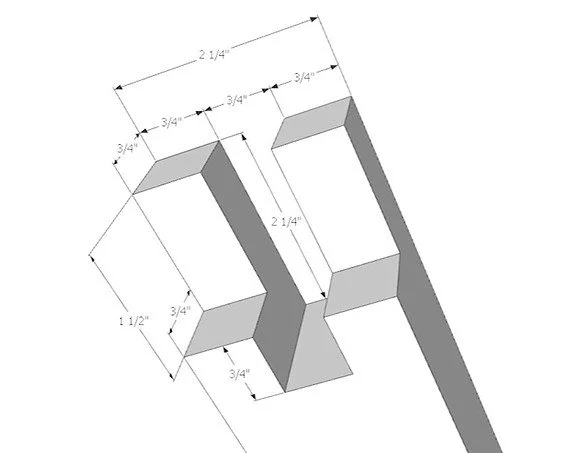

If you want a dimensioned drawing, below is one based on workpieces that are 1-1/2 inches thick and 2-1/4 inches wide—the same 1.5:1 ratio. Of course, if your workpieces are larger or smaller, you’ll need to recalculate these measurements, which can introduce error. That’s why it’s always best to use the workpieces themselves as gauges. Keeping this principle in mind will save you a lot of frustration in this craft, no matter what you’re making.

Dimensions for the joint based on workpieces that are 1-1/2 inches thick and 2-1/4 inches wide.

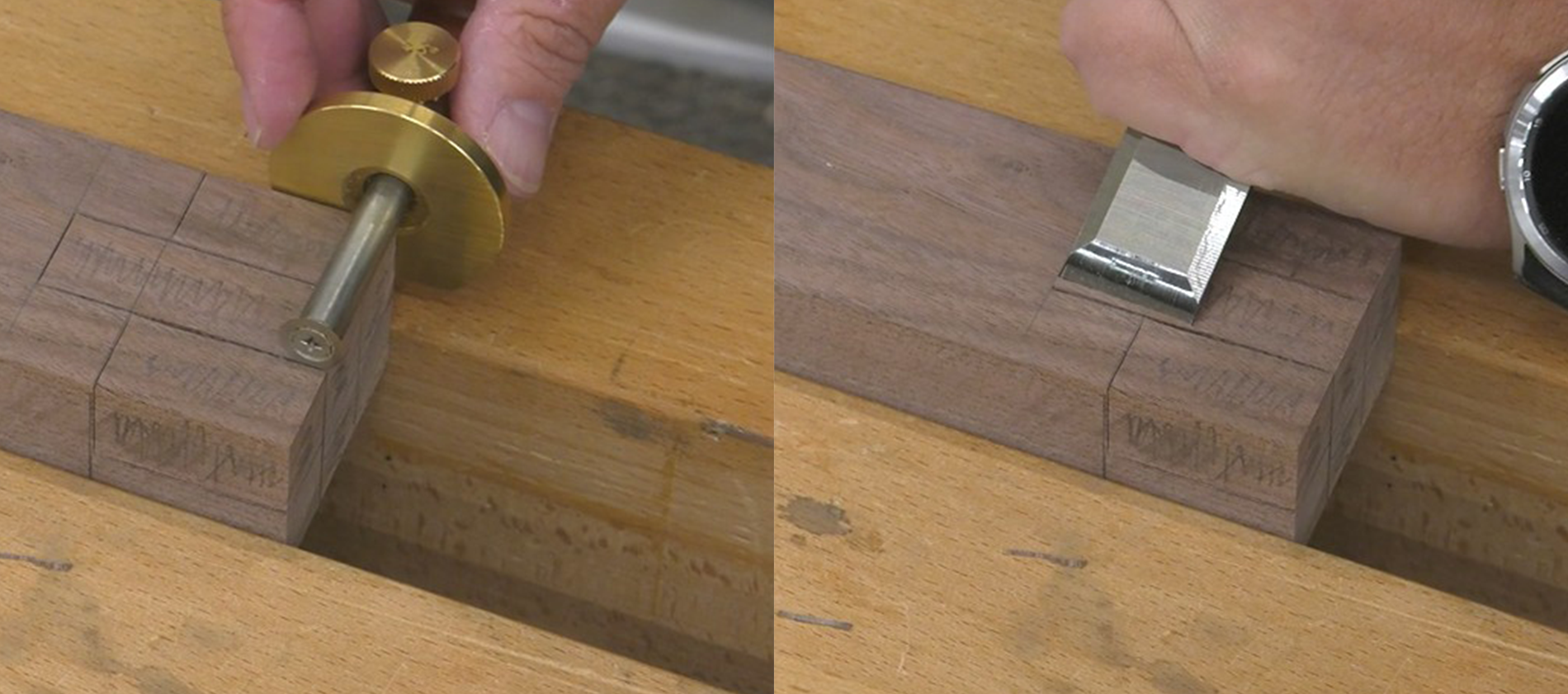

A Handy Tip: Cutting a Shoulder to Guide Your Hand Saw

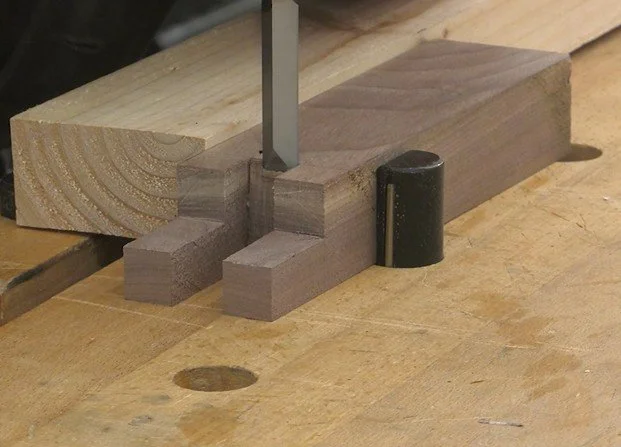

Another excellent tip that will help in numerous other projects is to cut a shoulder to guide your hand saw. To do this, use a knife or marking gauge to scribe over your lines, then follow up with a chisel on the waste side of those lines.

The chisel removes a small wedge of material, leaving behind a groove where your saw blade can drop and be guided. Since the saw naturally wants to follow the path of least resistance, these shoulders make it much easier to create nice, straight cuts.

The chisel removes a small wedge of material, leaving behind a groove where your saw blade can drop and be guided.

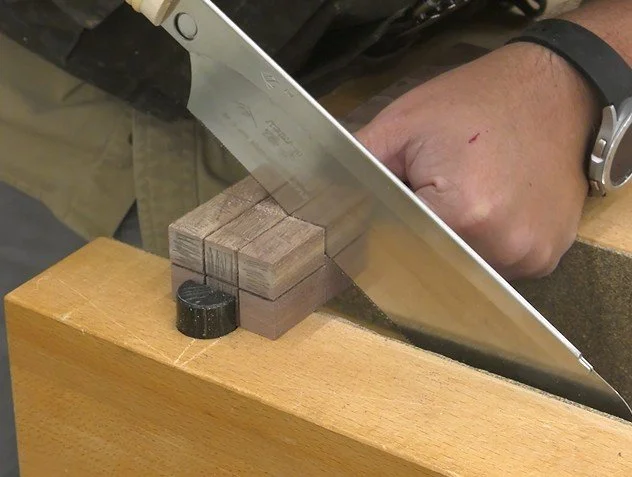

Despite all these lines, there are only four cuts to be made. The first one is right down the center of the end grain.

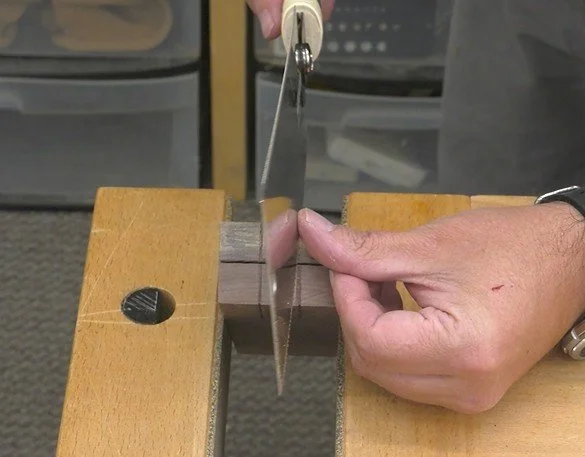

I angled the workpiece so I can see the line on the edge facing me, and the one across the end grain.

I angled the workpiece so I can see the line on the edge facing me, and the one across the end grain. I dropped the blade into that chiseled groove, where it naturally fits against the shoulder, right on my line. As I cut, I worked back and forth, taking light strokes while following that line down the edge, then across the end. Once I deepened the groove a bit more, I could speed up the cut, letting the kerf guide the saw, again down the edge and then back across the end.

Once I deepened the groove a bit more, I could speed up the cut, letting the kerf guide the saw, again down the edge and then back across the end.

After I connected the two opposite corners at this angle, I can reverse the workpiece in the vise and repeat the same process starting at the other corner. There’s no rush—take your time and don’t grip the handle too hard. Just relax and let the kerf guide the saw as you advance it deeper and deeper.

Finally, I set the workpiece straight in the vise and cut downward, removing the triangle of waste that remains inside. This finishing cut practically steers itself. Just don’t cut past your baseline.

With the first cut finished, I turned the workpiece 90 degrees in the vise and repeat the exact same process for the other two lines I scribed on the end grain.

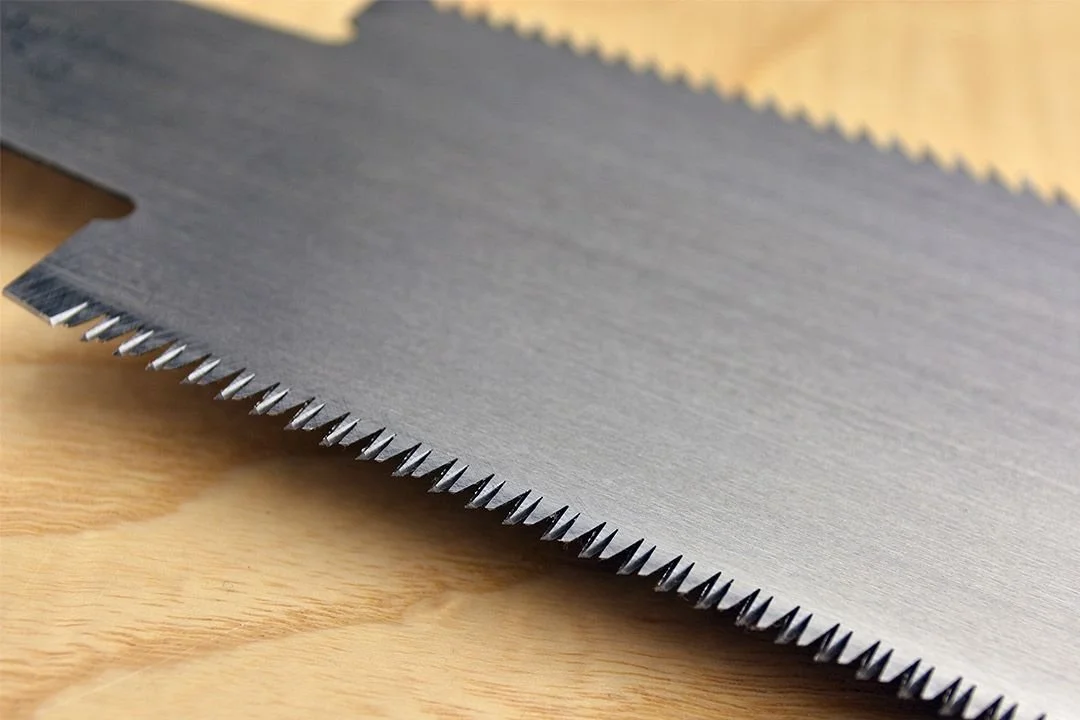

The Right Saw for the Job

This is a Japanese Ryoba (Rei-oba) saw, which is perfect for this type of joinery due to the rip teeth along one edge. There’s also no spine to impede a deep cut. It's not an expensive saw at all, and I think every shop should have one. I’ll put a link below to the one I use if you want to check it out.

One more cut—this time on the face of the workpiece. You’ll notice I used a different saw for this cut. I switched for two reasons: First, this is a crosscut, and rip-filed teeth aren’t ideal for cutting across the grain. Of course, a Ryoba saw does feature crosscut teeth on the opposite side of the blade, which is why it's so versatile. However, this saw, called a Dozuki, features a thinner blade that I find even more precise. But it has a spine, which limits the depth of the cut, and the teeth aren’t ground for ripping through end grain.

I did do one additional step that I don’t count as one of the four cuts in this joint because it’s not absolutely necessary. I used a fret saw to remove the bulk of the waste in the middle before I used a chisel. It’s a convenience, really. You could just chop it all out with a chisel alone, but I do recommend using a fret or coping saw if you have either available.

Using a fret saw to remove the bulk of the waste in the middle of the joint, for convenience.

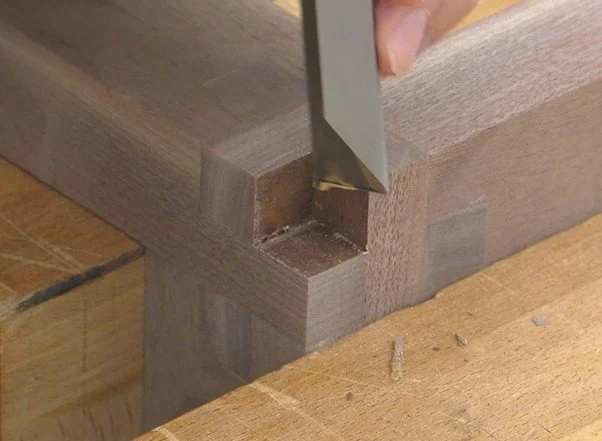

As I starting using a chisel, the shoulders I previously established continue to pay off. This time, they provided a positive stop to guide my blade as I chopped right on my line. If I hadn’t cut away most of that waste with the fret/coping saw, I’d have to chop it out in sections, working my way back to the final line so the excess waste doesn’t force my chisel out of position.

As I starting using a chisel, the shoulders I previously established continue to pay off.

Repeat this process on all four workpieces and do a dry fit. If everything looks good, you can slather on some glue, and it’s time to assemble them.

Assembling the Joint

The pieces go together a bit like a puzzle. One stands upright, facing me as you see here. The second is turned face up and inserted from the left. The third is turned 90 degrees and inserted from the back. Here’s a drawing that may help you visualize it.

As the glue swelled the wood, I did have to do a bit more pounding with the mallet than I would have liked. I’m lucky I didn’t split anything! And I used a lot more clamps than I really needed. But once it was dried and sanded a bit, it looked pretty nice. We’re not done yet, though.

That little empty spot at the corner has to be filled with a block of wood. I suppose you could leave it empty if you wanted to, but I think it looks better filled.

Adding the Finishing Touch

Once that's done, you have a nice, square joint. It looks great just like this, but there’s another modification I think makes it look even better.

I decided to saw off the corner along these lines, which connect the corners of the various segments. This compound-angled cut is a little tricky, but if you take your time and follow your lines, it’s not difficult.

Removing the corner adds more facets to an already complex look, and I really like it better this way.

I think this joint would be great for tables, chairs, benches, bed frames—you name it. And it is one of the strongest corner joints I have ever assembled.

3X3 Custom - Tamar's video: • This joint looks complicated, but it'...

(The links below are affiliate links. If you make a purchase, we may receive a small commission.)

Fisch forstner and drill bits: https://amzn.to/3KT440D

Ryoba hand saw- https://lddy.no/1447c

Dozuki hand saw- https://amzn.to/4iH0siU

Need some other cool tools for your shop? Browse my Amazon Shop for inspiration.