THE GREAT SCREWDRIVER WARS

It’s been more than 200 years since Canada and the United States fought a war against each other, and if it ever happens again, it won’t be over important issues like who has the best pancakes or the best version of Chris Farley. It will be over something that has divided not just North America, but the entire world for over a century: Which screwdriver is best—the Canadian Robertson head, or the American Phillips head?

While screwdrivers are among the most common household tools today, this is no casual choice between a square and an X. These two types of drivers are deeply embedded into their respective cultures through a dark past that includes involvement in two of the worst armed conflicts in recorded history and an incident involving the most powerful industrialist of the age, who sought to kill his competition to save a mere $2.65.

In this post, I’ll tell a short and fascinating version of the story and explain why Americans are still suffering today because of the Screwdriver Wars of a century ago.

It All Began with a Canadian Salesman

It all started with a Canadian salesman named Peter Robertson. In an era where everyone seemed to be trying to invent a better mousetrap, Robertson patented a few of his own ideas, including a mousetrap and a fancy corkscrew that nobody needed. Then, one day while demonstrating a spring-loaded screwdriver for a skeptical audience, the flat-headed bit slipped from the slot in the screw head and badly cut one of his best nose pickers.

Now, being Canadian, the first thing he did after presumably telling the screwdriver he was sorry and taking a shot of maple syrup to dull the pain, was start tinkering with some new ideas for a better screwdriver.

Of course, he wasn’t the first person to come up with this idea. A lot of folks before him had been driven to the task, including an American named Allan Cummings. Most people don’t know that Cummings invented the square screwdriver thirty years before the man who gave his name to it. Besides the square Robertson drive, Cummings also patented a retro triangular drive and a square-slot combo—a sort of three-for-one deal on questionable ideas.

The Questionable Beginnings of the Square Head

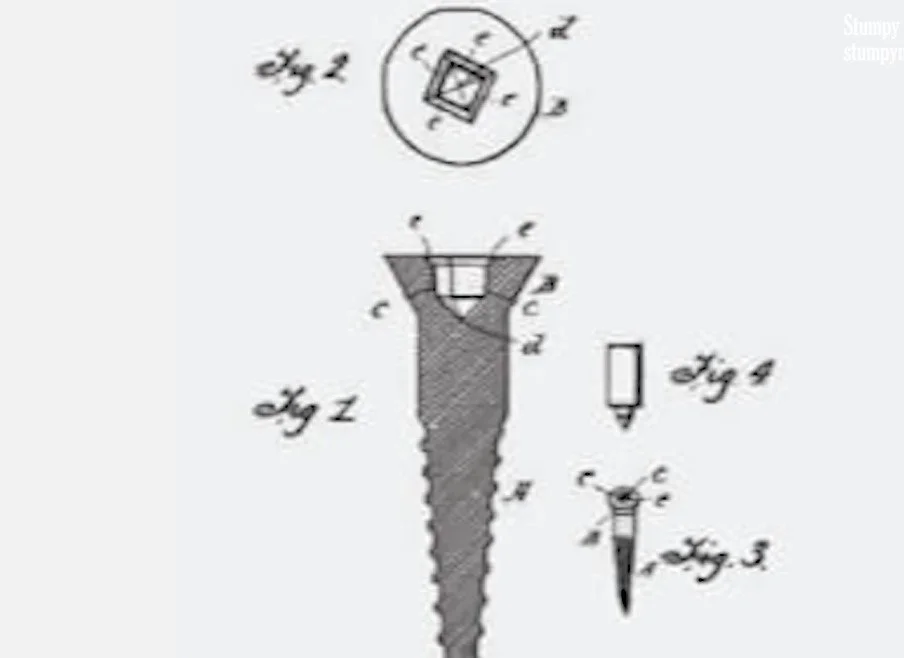

Why was the original square screwdriver a questionable idea? Because the manufacturing process involved stamping the shaped recess with a die, which had the unfortunate effect of deforming and weakening the screw head itself. Like many otherwise good ideas, this one simply proved impractical to manufacture on a large scale.

That’s when Robertson came along. He improved upon Cummings’ idea by tapering the sides of the square recess like a pyramid, a shape that could be cold-stamped into the screw without deforming the head—just like the Egyptians would have done if they had screwdrivers.

That was Robertson’s real contribution to the industry—not the idea of a square drive, but a way to make them quickly and cheaply by the billions. And for that, he got to slap his name on it and soon he was marketing his screws all over the great white north as a solution for everything that was wrong with screwdrivers.

Robertson’s Triumphs and Failures

Robertson was a slick salesman, but his screwdriver was objectively better. The square head is self-aligning and self-centering, making it faster and easier to operate the screwdriver with a single hand. The tool was also far less likely to slip, or “cam-out,” and damage the material around the screw. Furniture makers, boat builders, and anyone who worked on slippery things like butter churns and banana peelers loved the idea of a more secure match between screw and screwdriver.

But do you know who didn’t love the idea? The Kaiser and his minions sweeping a path of death and destruction through Europe. Actually, both sides of WWI needed plenty of screws, and Robertson tried his darnedest to make his square drive the choice of every Fritz, Tommy, and Doughboy in Europe. Sadly, many considered a Canadian screw a bit... knuckleheaded.

Henry Ford’s Offer and Robertson’s Refusal

As the war closed, Robertson’s idea caught the interest of automobile magnate and noted cheapskate, Henry Ford, when it was calculated that using Robertson’s screws could reduce the cost of a Model A by almost $3.

Ford made Robertson an offer he couldn’t refuse, including an exclusive contract to sell only to Ford, and the privilege of letting Ford dictate how they run their business and make their screws. Robertson refused the offer, and as a result, he not only lost out on the U.S. auto market but also lost the Canadian auto market and a third of his business. This was his second failure to license his screw design outside of Canada, and from that day forward, Robertson vowed that his screw would remain a product primarily for the Great White North. Even today, a century after Ford all but killed the Robertson screw, Canadians love their square heads like they love their pet polar bears, and hardly an igloo in the land isn’t held together with their beloved “Robbies.”

The Rise of the Phillips Head

Of course, the auto industry wasn’t just going to go back to their plain, flat-headed, hand-gouging slotted screws. They still needed a better solution. And that came a few years later with the development of a clever X or cruciform-shaped design, which we all know today as the iconic Freason head.

You read that right. History is full of lies. It was Cummings, not Robertson, who invented the square head, and it was Freason, not Phillips, who invented the cruciform head.

John Freason, an English inventor, patented his idea in the 1880s. But like Cummings before him, his idea was later improved upon by an American named John P. Thompson, and later brought closer to imperfection by his business partner, Henry Phillips.

Finally, America had its own screw, designed by Americans after originally being designed by an Englishman. But we know how to take credit in this country, and it was the third man in the process, Henry Phillips, who gave his name to what would become the most popular, poor design in the fastener world.

The Phillips Screw Takes Over

The rise of the Phillips screw was largely due to the same forces that turned against the Robertson. In the late 1930s, the auto industry adopted the design. When the industry switched from making cars to making planes and other weapons for WWII, Phillips screws went into everything. When Allied soldiers returned home, they demanded the same types of tools they were used to on the battlefield, and by the middle of the century, everyone seemed to be using Phillips, not just in the U.S., but in many other countries as well.

Phillips isn’t a perfect screw design by any stretch. It suffers from several significant flaws, including a frustrating tendency to cam out—the driver popping out of the recess. Remember, this was the main problem Robertson originally set out to solve. And who among us hasn’t experienced a Phillips bit popping out of a screw head and smashing into a finger, much like the accident that started the screwdriver war back in 1900?

The Debate Continues

But as it turned out, the world had changed by the age of the Phillips, and what was once seen as a flaw began to be viewed as a necessary feature for the pre-war manufacturing industry. A Robertson head might snap right off the screw when it is seated tightly into its hole. A Phillips screwdriver, on the other hand, could cam out when the screw became tight, preventing over-driving—while also increasing the risk of marring the area around the screw.

So the debate has continued. Even today, Canadians stubbornly hold onto their Robertson screws as hard as Americans do their feet. They repeat the same arguments—that Robertson screwdrivers are more secure in the screw recess, that they don’t strip and ruin the screw like a Phillips bit can, that they can be held on the driver more easily for one-handed operation, and so on.

Meanwhile, we Americans still try to classify our Phillips head’s tendency to cam out as a feature that was very useful half a century ago, before clutches and torque-adjustable drivers became common, and which is still favored by drywallers and a few others today. So what if they strip out easily and have to be extracted with special tools and a great deal of profanity? We are never going to admit that the Canadians can do something better than we can.

Conclusion

While Robertson screws have remained largely a Canadian phenomenon, they are available in many countries around the world, including in most hardware stores in the United States. But we still look at their strange square heads as a mere curiosity, as we reach past them for a box of Torx-headed screws and say, “Finally, a screw that won’t cam out. Why didn’t anyone think of that before?”