MANY WOODWORKERS USE THESE WRONG!

Do not let the fru-fru woodworking purists tell you that you can’t use biscuits, dowels, or pocket screws and still call yourself a woodworker. A good housebuilder doesn’t insist every wall be built from cut stone because not every wall needs to absorb a cannonball. The goal is to build something that is beautiful, functional, and durable. Those are the standards good woodworkers are measured by. How you achieve those standards is a personal decision.

I dovetailed this little box because I think it adds to its beauty and because I enjoyed the process. It even satisfied my ego a little bit, because I know some people will look at those well-cut dovetails and appreciate the skill that went into them. But the joinery on the top, which is essentially another small box, is simple bevels and glue. Is the top of this box inferior because the joinery is less advanced? Not at all. The bevels and glue, while a relatively simple and weak form of joinery, are still appropriate for the application. This box will last for generations if cared for.

My point is that we should not give in to the stigma that some purists try to attach to people who uses appropriate joinery for the project at hand. As long as that joinery satisfies the standards of beauty, function, and durability, then it is appropriate for the project.

That brings us to three very popular forms of joinery that get a lot of criticism from the self-appointed gatekeepers of the craft: biscuits, dowels, and pocket screws.

We’ll discuss them one at a time, including why you may choose one over the other, when you should use them, and when you shouldn’t. These next few minutes may just save your next project.

BISCUITS

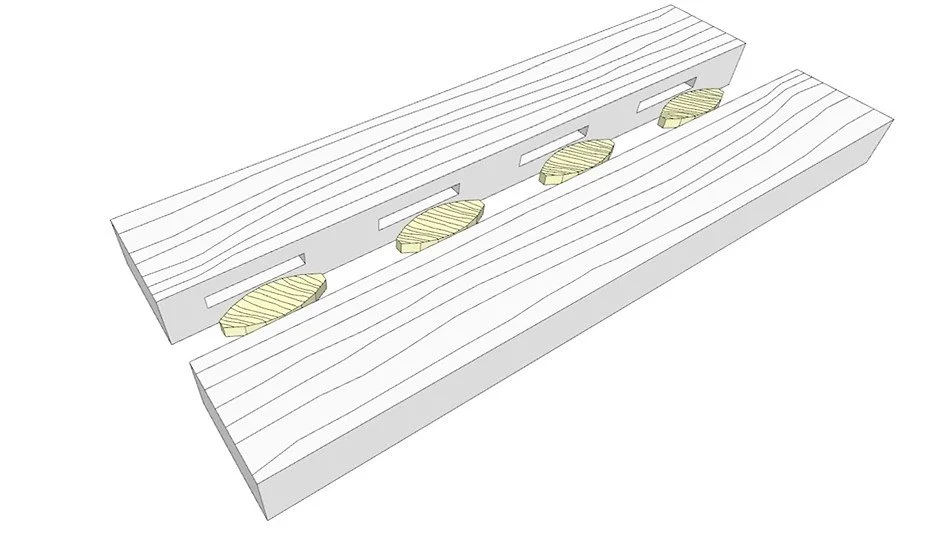

A biscuit is a piece of compressed wood that fits into a slot cut by a biscuit joiner, which is sometimes also called a plate joiner. Though invented in the 1950s, biscuits really became mainstream because Norm Abram used one regularly on The New Yankee Workshop in the 80s and early 90s.

Biscuits do add some strength to a joint because the grain direction of the biscuit runs perpendicular to the seam in the joint itself. Take an edge joint, for example. The grain of the two boards runs parallel to the glue seam. The weakness is not the yellow glue you use to bond the two edges together; it's the natural glue (lignin) inside the wood that holds the individual fibers together. For this joint to fail, the lignin in the wood must fail, allowing the fibers along the edge of the boards to split or break away.

A biscuit introduces perpendicular grain that runs across the seam. For this joint to fail, the lignin along the edges of the boards must fail, and the fibers in the biscuit must be severed. That’s not so easy.

I can break this biscuit along the grain easily, but there is no way I could break it across the grain with my fingers alone, even if I had more to hang onto, because the fibers themselves are much stronger than the lignin binding them together. It will break, but it takes a lot of leverage.

That’s the weakness of any joint: leverage. When enough leverage is introduced, any joint will fail. A biscuit is only 1/8-inch thick, so it takes less leverage to break a biscuit than it does to break a dowel, a pocket screw, or various forms of mechanical joinery such as dovetails and finger joints.

So, biscuits are best used in situations where little leverage will be exerted upon them. For example, a cabinet that will be fixed to a wall will see almost no racking forces at its corners. A biscuit may be a good choice in this situation.

On the other hand, other types of casework, such as a floor-standing cabinet or a bookshelf, may be moved around during its lifespan, and biscuit joints alone may not withstand all that stress. Table and chair legs especially must withstand a great deal of racking forces. A biscuit would be a poor choice in this situation.

Where biscuits shine is not so much for their added strength, but to help you align workpieces during glue-ups. This is where I use my biscuit joiner the most.

The bottom line on biscuits is that they are good for alignment purposes and for non-structural joinery, but not so much for structural joints that may see a lot of racking forces.

DOWELS

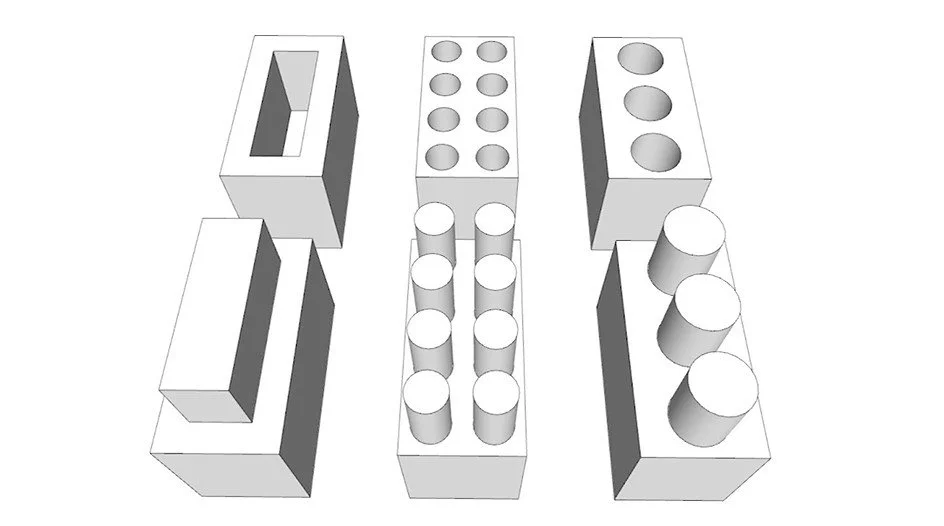

Dowels are significantly stronger than biscuits. They are essentially loose tenons, with each end fitting into a mortise. Like traditional mortise and tenon joinery, dowel joints can be very strong if they are properly made.

Dowels benefit from the principle of strength in numbers. I can break a 1/4-inch dowel fairly easily, but it is much more difficult to break a bundle of them. Likewise, one dowel may create a joint that's strong enough for a small project part, but larger workpieces may require larger dowels, or even clusters of dowels.

Do you see what I mean about dowels being very similar to traditional tenons? All three of these joints would be strong enough for virtually any furniture application, including structural joints on tables and chairs.

The problem with dowel joinery is that it must be very precise. It’s one thing to fit a single tenon into a single mortise; it’s another to fit several dowels into several mortises at the same time. Everything must align perfectly, and because you are drilling holes in both mating workpieces, alignment errors can compound quickly. Even if you manage to mash a poor-fitting dowel joint together, those inaccuracies can create gaps that compromise the glue bond.

To create strong, structural dowel joints, you need a very accurate jig. I use the Dowelmax, which is not a sponsor. It’s just a great jig from a great small business. I’ll link to it below this post. If you have a good jig, and you know how to use it properly, dowels are no different than dominoes when it comes to strength.

Where dowels fall short, in my opinion, is in convenience. It takes time to bore all those perfectly aligned holes, and the glue-up process can be messy.

POCKET SCREWS

Pocket screws are like metal dowels that require no complex alignment, and the glue is optional.

A pocket screw is many times stronger than a wooden dowel or a biscuit. I have never seen one of the screws themselves fail. The weakness of a pocket screw joint is the wood itself. While a dowel replaces any wood removed to create the holes, a pocket hole reduces the amount of wood around the screw head.

This is why you can’t cluster pocket screws together on the end of a rail like you can with dowels. You will remove too much wood when you create the pockets. That’s why I do not recommend pocket screws for high-stress structural joints, such as chair and table legs, where a lot of leverage may be applied.

But I love pocket screws for casework, including cabinet boxes, face frames, and built-in bookcases. Pocket screws are also very useful for solving difficult problems. Many times I’ve been able to slip a pocket screw into a tight spot to create a strong joint where conventional joinery would have been difficult or impossible.

Pocket screws also allow for some wood movement, making them useful for attaching solid wood table tops or other cross-grain joinery. They are wonderful for projects that you may wish to disassemble and modify at a later date because they can be used without glue.

Perhaps my favorite thing about pocket screw joinery is that no clamps are needed. In fact, I have used pocket screws in place of clamps to hold projects together while the glue in my conventional joinery dries.

Admittedly, pocket screws come with a big downside. Unlike dowels and biscuits that are concealed within their joints, a screw pocket is unmistakable. They may be plugged, but unless you plan to paint the project, their locations must be hidden through careful planning.

CONCLUSION

There are obvious pros and cons to all three types of joinery.

Biscuits are great for aligning project parts during glue-ups, but they add little structural strength to the project.

Dowels may be structurally strong when grouped together, but the holes must be precisely bored with an accurate jig.

Pocket screws are fast and easy for casework, face frames, and other joinery that will not be subject to a great deal of leverage, but the holes must be carefully hidden.

There is a time for dovetails, finger joints, rabbets, dados, mortises, and tenons. They are still the fundamental joints of furniture making, and in some cases, there is no substitute for good, traditional joinery. But when used properly, there is absolutely no reason why biscuits, dowels, and pocket screws shouldn’t have a place in your workshop as well.

Happy woodworking!

Tools used in this video:

Castle Pocket Hole Machine: https://castleusa.com/

Dowelmax dowel jig: https://www.dowelmax.com/

Links promised in this video: -More videos on our website: https://stumpynubs.com/

Check out our project plans: https://stumpynubs.com/product-catego...

Instagram: / stumpynubs

Twitter: / stumpynubs

Facebook: / stumpy-nubs-woodworking-journal-3056398594...

★THIS VIDEO WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY★

Castle Pocket Hole Machines https://castleusa.com/

Please help support us by using the link above for a quick look around!

(If you use one of these affiliate links, we may receive a small commission)